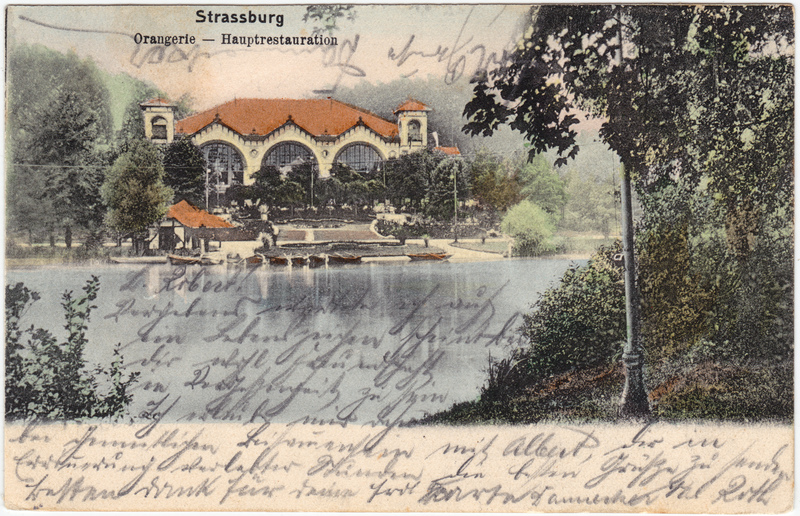

I recently discovered a collection of 160 poems written by Heinrich the cellist for his beloved Maria in 1903/04, within a year after meeting her at Strasbourg. In a previous blog entry I discussed the meta-information I gathered from the album, ie dates and places of their first year together (out of more than 50), based on a quick assessment of the work.

The frontispiece of Heinrich's poetry album.

As I have now transcribed the entirety of the poems (more than 16,000 words, which I think may be more than we have from Walther von der Vogelweide?) I can also analyse what is and what isn’t discussed.

Given the context of my musical memoir project, I was hoping to find mentions of any instruments that Heinrich may have been playing at the time, but was disappointed. There is no mention of cellos anywhere, and very few other instruments either. There is one mention of violins in a rather clichéd way to describe a party situation which our poet swiftly leaves behind. One fiddle I will discuss below. One mention of a harp as a metaphor for women being sensitive (can’t help sounding when I’m touched), a few bells ringing, and that’s about it. Otherwise music mostly comes in the shape of singing, which can have strong emotional impact.

There are a couple of poems I found quite interesting in that they are elaborating on the strong impact of a song or melody on a person’s mind. One rather haunting example is about a young soldier who gets executed for deserting his post. It turns out that he was alone on his watch when a passing craftsman sang a song to himself, and this reminded him so much of his home and the loved one he left behind that he couldn’t help himself, left his post to head home. I found it quite a remarkable piece of writing, considering the author was both a soldier and a musician at the time, describing a deadly outcome of conflicting loyalties between these two identities. A similar story is also told in the song "Zu Strassburg auf der Schanz": In the late 19th century version with music from Gustav Mahler, which Heinrich may have known, an alphorn inspires a soldier of Swiss origin to desert.

The other is written in the voice of a woman who comes across a travelling musician, whose fiddle playing reminds her of somebody she knows and makes her long for that absent person. It's not the only one written in a female voice. Although only four poems are in Maria's handwriting, I wonder to what extent she may have contributed to those, eg by sharing her experiences, impressions, views.

In many other poems, the music of nature, eg winds, waves, streams, birds singing does have an emotional effect, and a few of the poems are marked as songs (but missing the dots).

There is a lot of nature going on, with forests, rivers, mountains and all the rest of it, but no specific geography of any sorts. No specific river, mountain or place is mentioned in any of the poems, although some are marked as having been written in response to specific events at specific places.

There are way too many flowers for my taste, including some I didn’t know, but mostly the usual suspects from roses to forget-me-nots. Maria is guilty of that as well, one of the four texts she has contributed is about flowers too. There were also some small flowers pressed between the pages.

As I was transcribing some of these poems while some soggy pop ballads were playing on the radio, it struck me that they were really very similar. A lot of the material reads like listening to “Eternal flame” on closed loop. In defence of Heinrich the young poet, however, we have to remember that when he was writing, in 1903/04, there was no recorded music, no radio, no pre-fabricated entertainment of any description. Thus, all the things that we’ve come to regard as clichés after decades of overexposure to industrially manufactured love songs, including the rhyming couple of Herz and Schmerz made notorious by German Schlager, would have sounded a lot less worn out back then. And there are some nice original ideas too.

As a poet he is a slightly belated but unashamed romanticist, he even wrote one poem about the blue flower, which is a key symbol of German romanticism attributed to Novalis (Die blaue Blume). While literary romanticism was well and truly over before Heinrich was even born, Romantic composers were still going strong, so I guess as a young musician in love he should be allowed a bit of romanticism in his poetry too. Spoiler alert: he found the blue flower in Maria’s eyes.

Beginning of the blue flower.

Thankfully, there is no testosterone poisoned patriotism on display anywhere. Quite the contrary, our young poet comes across as the quiet and sensitive kind, so that's kind of a relief. Quite a few poems with titles such as "Mahnung" are advising the reader on how to be a good person - these remind me of Albert Schweitzer, who was at Strasbourg at the same time (1893-1913). Conceivably, Heinrich and Maria may have heard his sermons in St. Nicolas church (close to the hospital where Maria worked) and/or his organ playing.

All of this has required another additional sub-chapter to my Heinrich chapter (PDF here and also here), so the Strasbourg years are now covered quite well (and I am quite obsessed with Belle Epoque Strasbourg now), even though I am still in the dark re any musical activities.

The scans I made of the handwritten pages are now on Google Drive in two parts, see Part 1 (37 double pages), Part 2 (26 double pages). I have formatted my preliminary transcription on double pages to match the page spreads and uploaded them here and also here. If and when I get a chance to edit those PDF scans, I will be aiming to produce a version where original and transcription can be viewed on facing pages.

Heinrich's musical initials under one of the poems, with the notes H (B in international nomenclature) and G identified by the ledger lines below the (imagined) staff. Note that this idea seems to be pointing to a violin and/or guitar player - I can't play those notes on the flute and they wouldn't be written that way for cello or piano.